Um Al Naar

September 18 – November 23, 2019

The Third Line, Dubai

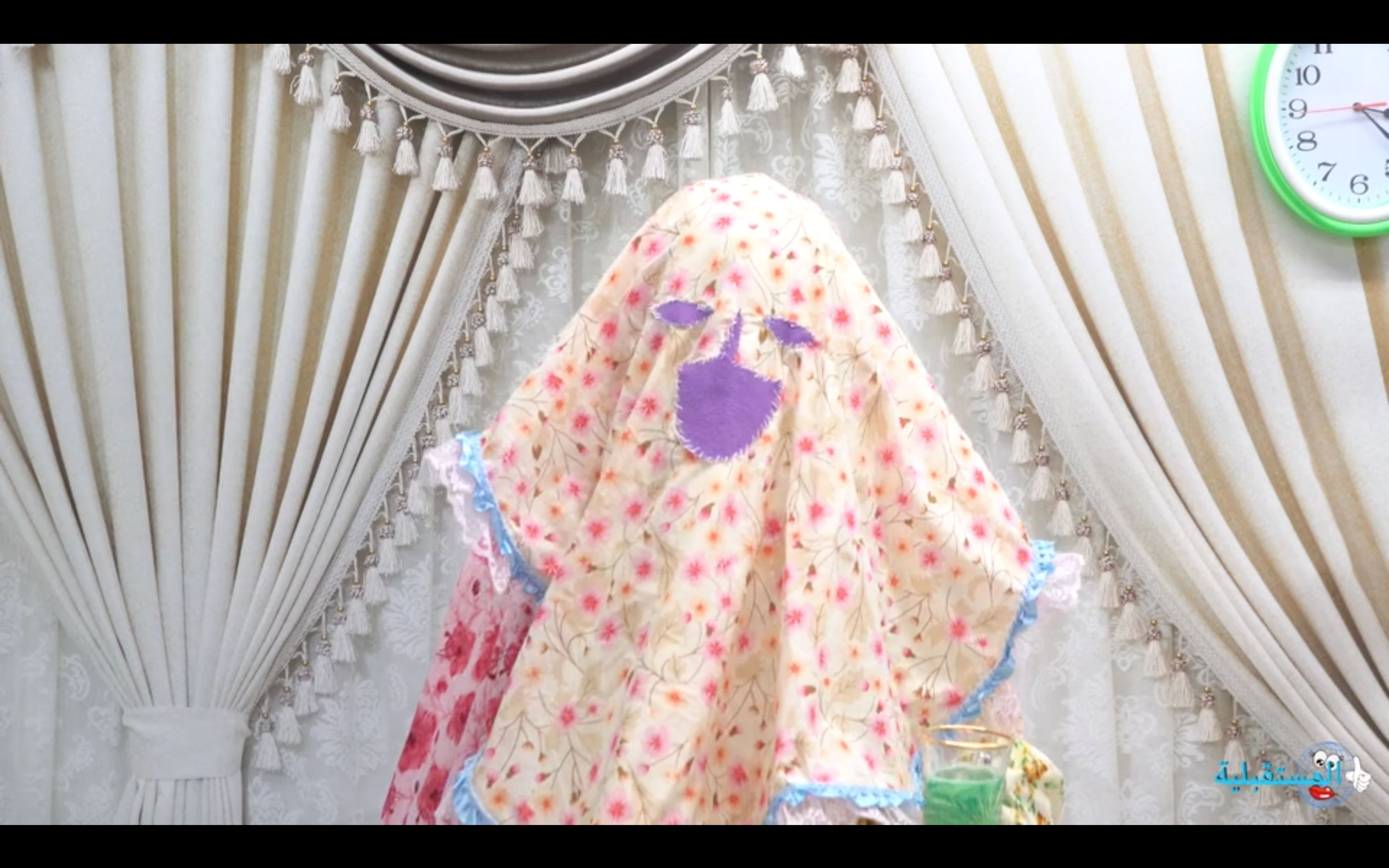

Arrival, Farah Al Qasimi’s third solo exhibition at The Third Line. Using the language of horror cinema, Al Qasimi reveals a new body of work featuring jinn folklore across the UAE.

The show premieres Farah’s first feature-length film; a 40 minute horror-comedy titled Um Al Naar (Mother of Fire). In it, a fictional Reality TV network has produced a segment on Um Al Naar, a Ras Al Khaimah-based Jinn. Um Al Naar narrates the region’s changes from its occupation by Portuguese and British naval forces to its current adoption of a national identity based around tolerance and a drive to generate culture. She pays close attention to these changes in their day-to-day iterations: the gendered pastimes of the country’s youth, waning trust in traditional forms of spirituality and medicine, and the loss of history in an urgent bid for novelty.

The photographs in the exhibition are moments pulled from the world she describes. She follows a baker with an Instagram business making buttercream roses, dance parties in which the only participants are men, and moves throughout homes looking at indicators of bodies and their personal style. Um Al Naar laments the formalities and social constructs of modern-day life, longing for a more fluid, interconnected world in which there is ample space for the paranormal, the unseen, and the absurd.

The film is peppered with found footage of various moments of release: exorcisms gone wrong, ecstatic dancing, and effervescent first-person storytelling. But as we lose our sense of collective release, Um Al Naar asks: ‘how do we attain bodily transcendence in a modern world?’

In many horror films, the antagonist we fear the most is invisible; not a spooky ghost or monster, but a figment of our collective unconscious manifested as immaterial danger. Many of Farah’s photographs contain a looming sense of dread or entrapment, even as the world they depict is full of color and cheer. A woman takes photographs in an aviary filled with live birds, their movement curtailed by a drop ceiling with fluorescent lights. A figure is reflected in a picture frame, her ghost trapped within its confines.Um Al Naar provides a space where these fears can be confronted—and where specters can move freely in bodily release.

The Third Line, Dubai

Arrival, Farah Al Qasimi’s third solo exhibition at The Third Line. Using the language of horror cinema, Al Qasimi reveals a new body of work featuring jinn folklore across the UAE.

The show premieres Farah’s first feature-length film; a 40 minute horror-comedy titled Um Al Naar (Mother of Fire). In it, a fictional Reality TV network has produced a segment on Um Al Naar, a Ras Al Khaimah-based Jinn. Um Al Naar narrates the region’s changes from its occupation by Portuguese and British naval forces to its current adoption of a national identity based around tolerance and a drive to generate culture. She pays close attention to these changes in their day-to-day iterations: the gendered pastimes of the country’s youth, waning trust in traditional forms of spirituality and medicine, and the loss of history in an urgent bid for novelty.

The photographs in the exhibition are moments pulled from the world she describes. She follows a baker with an Instagram business making buttercream roses, dance parties in which the only participants are men, and moves throughout homes looking at indicators of bodies and their personal style. Um Al Naar laments the formalities and social constructs of modern-day life, longing for a more fluid, interconnected world in which there is ample space for the paranormal, the unseen, and the absurd.

The film is peppered with found footage of various moments of release: exorcisms gone wrong, ecstatic dancing, and effervescent first-person storytelling. But as we lose our sense of collective release, Um Al Naar asks: ‘how do we attain bodily transcendence in a modern world?’

In many horror films, the antagonist we fear the most is invisible; not a spooky ghost or monster, but a figment of our collective unconscious manifested as immaterial danger. Many of Farah’s photographs contain a looming sense of dread or entrapment, even as the world they depict is full of color and cheer. A woman takes photographs in an aviary filled with live birds, their movement curtailed by a drop ceiling with fluorescent lights. A figure is reflected in a picture frame, her ghost trapped within its confines.Um Al Naar provides a space where these fears can be confronted—and where specters can move freely in bodily release.