Toy World

27 February - 19 April 2024

The Third Line, Dubai

If I go to Google and ask it to define “actor,” I am greeted with the following secondary definition: “a person who behaves in a way that is not genuine.” The example sentence illustrating this definition: “in war one must be a good actor.” Ipso facto: IN WAR ONE MUST BEHAVE IN A WAY THAT IS NOT GENUINE. They say we live in a post-truth era, but this reads like a Jenny Holzer Truism.

Actors in the theater of war go the way of images. An image can never be genuine. By default, it frames, excludes, contorts, seeks to represent: it must be ideological. Our relationship with images is reflexive: as images represent ideology, so our ideology is formed through images. An image begs to be interpreted. So a photo shorn of context is like a rose with no petals, only thorns. The rise of artificial intelligence portends that we must also contend with fake images. These are fake roses with real thorns and no petals.

Farah’s images are both real: organically taken in-the-world — and “fake”: staged, in her studio or elsewhere. Yet herimages, both real and “fake,” are all petals and no thorns. The unreality of contemporary life is inaugurated to the echelon of art object. In looking at these photographs, we role-play the time we spend looking at images online, unable to discern what is real and what is constructed: fact and fiction become two in one flesh, the orchestrations of fiction inoculating fact inoculating fiction, on and on recursively — just as history repeats itself over and over, when we do not listen, until it grows hoarse (Tumbling Woman, 2023). The information superhighway paves the path for the Highway of Death. The fiction of images can take us to the fact of war.

Actors are treated like toys: the theater of war, arbitrated by images, adopts the levers of entertainment (Toy War, 2023). Pundits give the layperson a play-by-play. They want us to watch, enraptured. They speak of sides as if we were at a football game. The more outrageous the coverage they ejaculate, the higher the ratings. A highly rated president wins a second term.

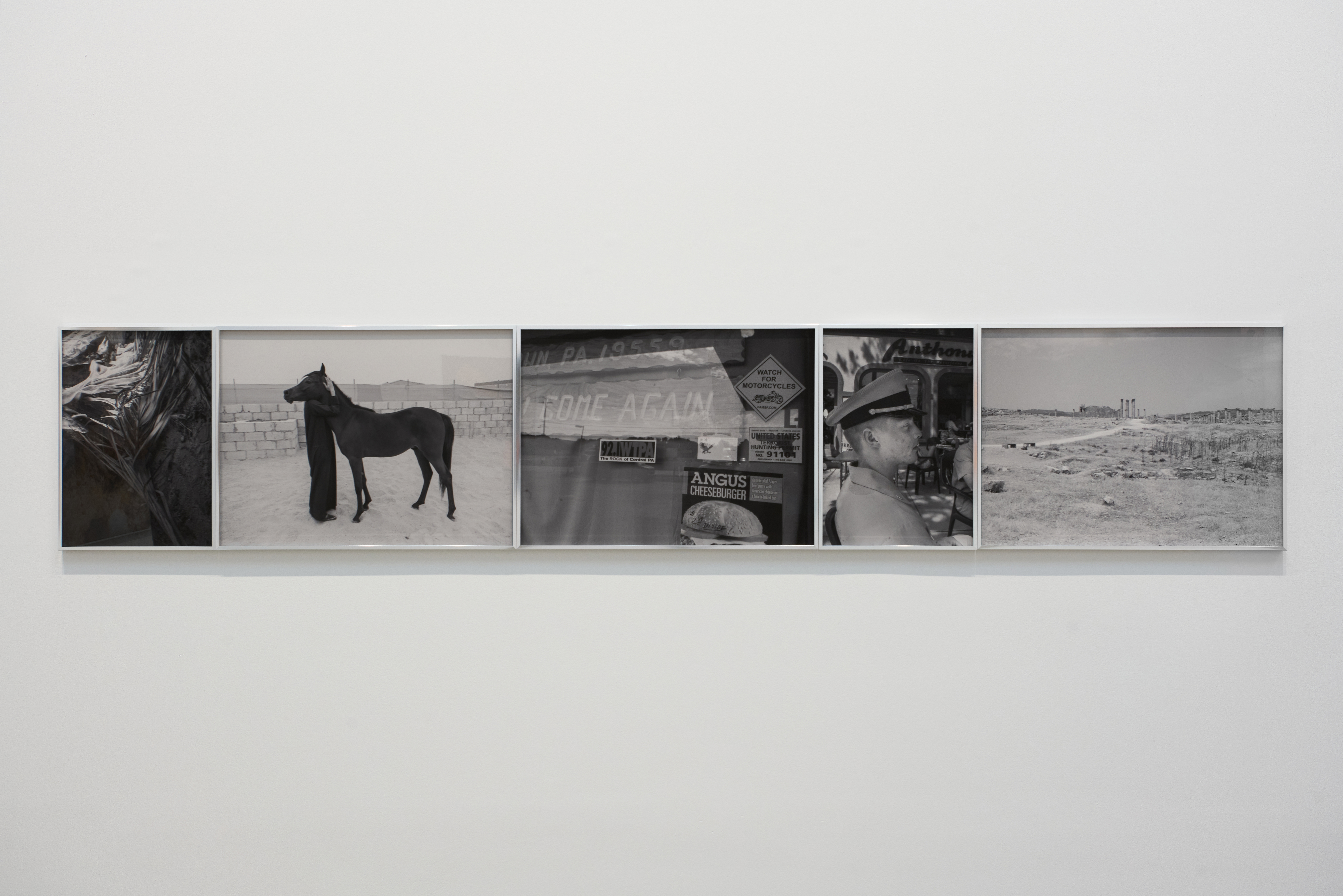

To become a highly rated president, you must responsibly govern your nation-state. A responsible nation-state must always be ready for war (Young Marine, n.d.). Paranoia flowers under the pretense of defense. Hunting is what you do to a wild animal before you skin them, dress them, and eat them. The United States grants itself a TERRORIST HUNTING PERMIT. It is a lifetime license. The threat can never be annihilated. It will last multiple lifetimes. This is red-blooded Americana, as American as a flamebroiled Angus beef patty with American cheese on a hearth-baked bun (Terrorist Hunting Permit, n.d.).

Some animals can sense changes in the environment that escape humans. Some, like horses, can even forecast natural disaster (Man and Horse, n.d.). Humans are sense-making creatures, too. They are the only species that wage the material disaster of war. This is the age of the anthropocene.

The palm tree is a parable of history: some trees live for over a century, spanning wars come and gone, humans born and dead. Like a palm tree left uncared for, or an empire caught up in its own decadence, the human imagination, too, is combustible, degenerating into flames under suboptimal conditions, like fear.

If blood spills (9/11), then the danger (terrorism) is real: so more blood must be spilled (Operation Iraqi Freedom) to annihilate the danger (Oriental Boulevard, n.d.). In this blood pact with safety, we must spill BLOOD to insure SAFETY. So, too, is the haematophagous fly drawn to the scent of a camel’s blood, feeding on it to stay alive (Flies on Camel, n.d.).

Arab Gulf women are known to wear heavy makeup. Women exchange the phrase ‘wishik yohmoul,’ — وشك يحمل— meaning your face and coloring can handle heavier makeup. This is also the manifestation-qua-lullaby the God-state whispers to itself every night. The state does itself up in the cosmetics of false victimhood, building itself up upon a foundation of fear, priming its subjects to numb themselves to death, concealing human rights violations (Crane Accident, 2017), highlighting the evil of the enemy, blending murder into righteousness, lining its eyes with the kohl of increasingly invasive surveillance systems (Yara, 2023).

A horse bucks when it senses danger and fears it cannot escape (Horse Bucking Teeth, n.d.). When danger is real, fear abounds. The powers that be recognize it as ammunition for a system of control. State becomes God. You enter the always-panopticon, subject to forever surveillance that does not guarantee safety any more than a fake security camera from the local dollar store. (Security Camera, 2017).

This is Farah’s first exhibition featuring black and white images. “Black and white images automatically historicize,” she says. The glossy veneer of history allows us to indulge in theory immune from personal responsibility. Too often, we forget that the now we live is but prototype for future history.

The carrier pigeon, once used by the military to deliver messages, is now obsolete. And yet a trace of the true self exists in the new self: her descendent, the city pigeon, is itself a message — that of the enshittification of the messages in the images that surround us (Pigeons on Pink Building, 2024).

We decode messages in the images we obtain through multiple degrees of separation necessarily mediated by a trust in the network. We do not have access to the reality that dances forth the images: we must content ourselves with only the images. Eventually, the choreography halts (Baton Girls, 2019). The image-flood makes it easy to feel nothing when confronted with reality in the second degree. The luridity of pain is no longer inherited. Yet the ghosts of the images penetrate our consciousness, reverberating ad infinitum: chicken bones in basmati rice take on the aura of death by drone (Machboos, 2024). I know that the camel bones lying in the barren grass are innocuous victims of the cycle of life, but all I can think of are anonymous human remains, lying forgotten in decimated battlefields that will never bear another rose (Camel Bones n.d.).

Yet all we have are our sigils, these images. Without them, we lie alone, prostrate in the desert under a starless sky (Sand Dune, 2023).

Text by Sarah Chekfa

The Third Line, Dubai

If I go to Google and ask it to define “actor,” I am greeted with the following secondary definition: “a person who behaves in a way that is not genuine.” The example sentence illustrating this definition: “in war one must be a good actor.” Ipso facto: IN WAR ONE MUST BEHAVE IN A WAY THAT IS NOT GENUINE. They say we live in a post-truth era, but this reads like a Jenny Holzer Truism.

Actors in the theater of war go the way of images. An image can never be genuine. By default, it frames, excludes, contorts, seeks to represent: it must be ideological. Our relationship with images is reflexive: as images represent ideology, so our ideology is formed through images. An image begs to be interpreted. So a photo shorn of context is like a rose with no petals, only thorns. The rise of artificial intelligence portends that we must also contend with fake images. These are fake roses with real thorns and no petals.

Farah’s images are both real: organically taken in-the-world — and “fake”: staged, in her studio or elsewhere. Yet herimages, both real and “fake,” are all petals and no thorns. The unreality of contemporary life is inaugurated to the echelon of art object. In looking at these photographs, we role-play the time we spend looking at images online, unable to discern what is real and what is constructed: fact and fiction become two in one flesh, the orchestrations of fiction inoculating fact inoculating fiction, on and on recursively — just as history repeats itself over and over, when we do not listen, until it grows hoarse (Tumbling Woman, 2023). The information superhighway paves the path for the Highway of Death. The fiction of images can take us to the fact of war.

Actors are treated like toys: the theater of war, arbitrated by images, adopts the levers of entertainment (Toy War, 2023). Pundits give the layperson a play-by-play. They want us to watch, enraptured. They speak of sides as if we were at a football game. The more outrageous the coverage they ejaculate, the higher the ratings. A highly rated president wins a second term.

To become a highly rated president, you must responsibly govern your nation-state. A responsible nation-state must always be ready for war (Young Marine, n.d.). Paranoia flowers under the pretense of defense. Hunting is what you do to a wild animal before you skin them, dress them, and eat them. The United States grants itself a TERRORIST HUNTING PERMIT. It is a lifetime license. The threat can never be annihilated. It will last multiple lifetimes. This is red-blooded Americana, as American as a flamebroiled Angus beef patty with American cheese on a hearth-baked bun (Terrorist Hunting Permit, n.d.).

Some animals can sense changes in the environment that escape humans. Some, like horses, can even forecast natural disaster (Man and Horse, n.d.). Humans are sense-making creatures, too. They are the only species that wage the material disaster of war. This is the age of the anthropocene.

The palm tree is a parable of history: some trees live for over a century, spanning wars come and gone, humans born and dead. Like a palm tree left uncared for, or an empire caught up in its own decadence, the human imagination, too, is combustible, degenerating into flames under suboptimal conditions, like fear.

If blood spills (9/11), then the danger (terrorism) is real: so more blood must be spilled (Operation Iraqi Freedom) to annihilate the danger (Oriental Boulevard, n.d.). In this blood pact with safety, we must spill BLOOD to insure SAFETY. So, too, is the haematophagous fly drawn to the scent of a camel’s blood, feeding on it to stay alive (Flies on Camel, n.d.).

Arab Gulf women are known to wear heavy makeup. Women exchange the phrase ‘wishik yohmoul,’ — وشك يحمل— meaning your face and coloring can handle heavier makeup. This is also the manifestation-qua-lullaby the God-state whispers to itself every night. The state does itself up in the cosmetics of false victimhood, building itself up upon a foundation of fear, priming its subjects to numb themselves to death, concealing human rights violations (Crane Accident, 2017), highlighting the evil of the enemy, blending murder into righteousness, lining its eyes with the kohl of increasingly invasive surveillance systems (Yara, 2023).

A horse bucks when it senses danger and fears it cannot escape (Horse Bucking Teeth, n.d.). When danger is real, fear abounds. The powers that be recognize it as ammunition for a system of control. State becomes God. You enter the always-panopticon, subject to forever surveillance that does not guarantee safety any more than a fake security camera from the local dollar store. (Security Camera, 2017).

This is Farah’s first exhibition featuring black and white images. “Black and white images automatically historicize,” she says. The glossy veneer of history allows us to indulge in theory immune from personal responsibility. Too often, we forget that the now we live is but prototype for future history.

The carrier pigeon, once used by the military to deliver messages, is now obsolete. And yet a trace of the true self exists in the new self: her descendent, the city pigeon, is itself a message — that of the enshittification of the messages in the images that surround us (Pigeons on Pink Building, 2024).

We decode messages in the images we obtain through multiple degrees of separation necessarily mediated by a trust in the network. We do not have access to the reality that dances forth the images: we must content ourselves with only the images. Eventually, the choreography halts (Baton Girls, 2019). The image-flood makes it easy to feel nothing when confronted with reality in the second degree. The luridity of pain is no longer inherited. Yet the ghosts of the images penetrate our consciousness, reverberating ad infinitum: chicken bones in basmati rice take on the aura of death by drone (Machboos, 2024). I know that the camel bones lying in the barren grass are innocuous victims of the cycle of life, but all I can think of are anonymous human remains, lying forgotten in decimated battlefields that will never bear another rose (Camel Bones n.d.).

Yet all we have are our sigils, these images. Without them, we lie alone, prostrate in the desert under a starless sky (Sand Dune, 2023).

Text by Sarah Chekfa